Artist Gê Viana grew up hearing from her maternal grandfather about the capelobos, creatures with men’s bodies, anteater’s snouts and bottle-bottomed feet, which live in the forest and hunt for dogs, cats and newborns for food. This popular indigenous legend, which has variations in Maranhão and Pará, despite scaring her, also came as a memory in her own body. “I have a very strong relationship when I enter the forest, in places where it is not common for anyone to be. You end up feeling that you belong to something, to a Brazilian history,” she tells seLecT.

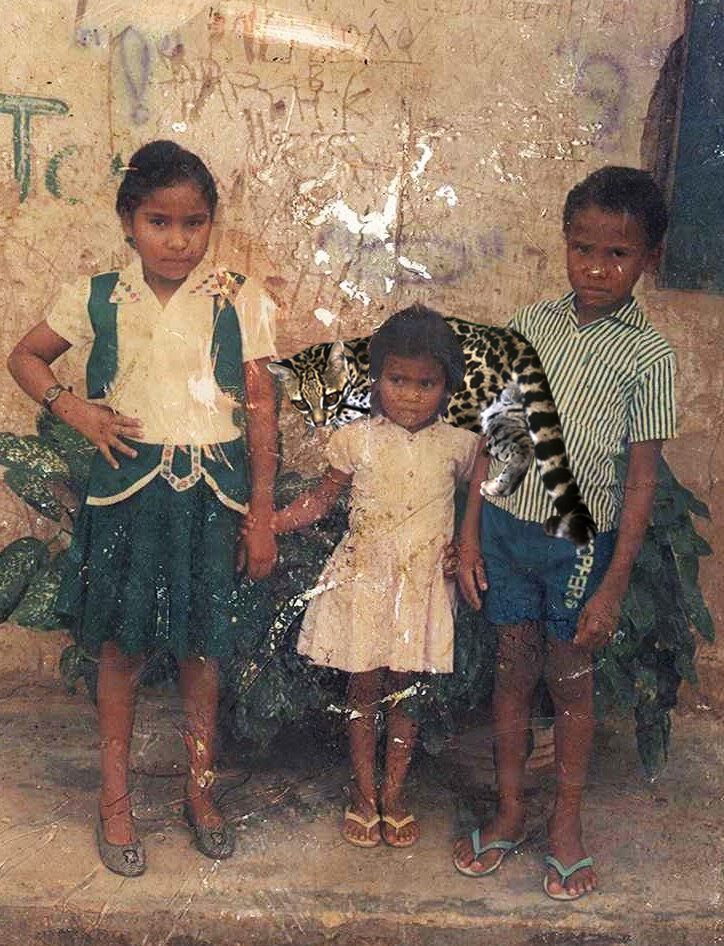

Due to her phenotype, the artist was questioned by a friend about her ancestry and decided to ask her maternal grandmother, Maria José, if there were indigenous people in the family. The answer she heard (about a woman who had been “caught in the bush”) has been guiding her trajectory ever since, around the understanding of her own ancestry. The artist, who worked with theater and performance before studying visual arts at the Federal University of Maranhão, which she joined in 2017, began that same year to produce the series Paridade. The photomontages are made by superimposing portraits of people from her own circle, in different locations in Maranhão, with images of representatives of different ethnicities. Among the characters in the series are aunt Raimunda, her grandmother’s older sister, paired with a woman from the North-American Pawnee Squaw people, and grandfather Fernandes, whose image merges with that of a native of the Amazon photographed by a Mexican, Dominic Bracco.

Her maternal great-grandparents (José Vitorino Ferreira Viana and Torcata Francisca Viana) were born on the banks of the Parnaíba River, in the city of Buriti, and for some time Gê Viana thought they belonged to the Guajajara people, an ethnic group that predominates in Maranhão. After much research, she understood that the city of Brejo, close to where her family lived, was the territory of the Anapurus people, also known as Muypurás. This research even resulted in the first meeting of Anapuru Muypurá relatives, in February 2021, which was important for the movement to retake the history, culture and resistance of the villagers in the Lower Parnaíba River region. The meeting was made possible thanks to the involvement of art educator Lucca Muypurá. Together, they are collecting and making available a series of documents and information on Instagram.

Along the way, the artist discovered that the people to which she belongs lived from farming. “The house where I was born was built with sacks of rice from a plantation my father made. It’s a people of harvest, not of war, of hunting,” she says. In her work, the search for ancestry shows up continuously, in works that explore the threshold between reality and fiction, such as Retiro de Caça (Hunting Refuge, 2019). There, through the fictionalization of legends from Maranhão, the Capelobo becomes an element of protection for violated indigenous and black women. Gê Viana is increasingly concerned with associating textual production with visuality, with talking “about what happened to our people far from their place of origin.”

Her desire is to create a book with these personal stories, which intertwine with the history of the Anapuru people. “To reprint the almost lost, to shred it until you notice the finger’s flesh sinking under the friction of the stylus. It is the continuation inherited by the Tapuias (a term of Tupi origin used at the beginning of Brazil’s colonization to designate indigenous people who did not speak ancient Tupi); I wash myself from the sun in the city so as not to leave this memory that wasn’t even mine, but now it is,” writes Gê Viana in a text for the Convida project, at Instituto Moreira Salles.

Exile

The artist’s research has points of contact with the one by Gustavo Caboco, born and raised in Curitiba, who became close to the Wapishana people only in his adolescence, since his mother left the Canauanim village as a child, in 1968, spending a period in foster homes in Boa Vista and Manaus, before being effectively adopted by a family from Curitiba. About this episode narrated by his mother as “adoption”, Caboco prefers to use the words “kidnapping” and “exile”.

His relationship with the village takes place in two stages: listening to his mother narrate the children’s games on the stream and, later, when visiting the place for the first time and understanding what he was hearing. “When I went there, I noticed my differences in relation to my mother’s context, but also in relation to my context. If, before, I already felt that my life was marked by differences, the same happened when I got to know my relatives – I was also different from them, because I grew up in another place,” says Gustavo Caboco to seLecT.

The choice of the artistic name Caboco is an offshoot of this feeling. “This word shifts the indigenous identity to the caboclo, as if you could no longer be indigenous and were the caboclo.” That’s how the farmer calls them, to disqualify them, but I tried to make an inversion of view, the displacement as a place of dialogue, between Gustavo, Caboco and Wapishana,” he explains. “The white system of thought ends up using the artifice of mixing to deny or erase roots, so, for me, this caboco only makes sense if I am in a dialogue with the Wapishana.”

Caboco, like Gê Viana, aims to record this story through image and writing. Both have learned another way to relate, in the transition from the individual search to the collective process. The turning point, in the case of the Curitiba artist, was the participation in the Tamoios Contest, in 2018, when he was able to get closer to a group of indigenous writers and, from there, began to delve into the history of his family members – among them the uncle Casimiro Cadete, who, on his visit to the village, presented him with a Wapishana-Portuguese dictionary. “I was already working to understand my indigenous issues, but I was living outside of any kind of circuit. I didn’t grow up in a context of relationship with indigenous people, except my mother. I have always been on the sidelines, with a lot of confusion in this belonging,” says the artist.

Return to earth

In the text presented on the occasion, entitled A Semente de Caboco (The caboco seed), he starts from the attempts to organize this story, exploring through drawing and poetry issues of silencing and lack of listening. “Return to Earth” is the name given to his creation process, which involves both an attempt to amplify the voice of the Wapishana people and a journey to his own origins. The moving body is present throughout his work and appears literally in Plantar o Corpo (Plant the body, 2017), in which the artist registers himself in a sequence of two images: in the first, he is lying on a sandy ground; in the second, he appears immersed in a waterfall, merging with nature.

In the process of preparing for his participation in the 34th São Paulo Biennial, Caboco met at the end of 2020, in Rio de Janeiro, with a Wapishana work team, which includes historian Roseane Cadete, anthropologist Paula Berbert, photographer Wanderson Cadete, in addition to his mother, Lucilene Wapishana, and a child artist, only 9 years old. “My relatives came from Roraima, my mother and I left Curitiba and we are at this meeting point, looking at the Imperial River and the crossings from a historical point of view,” says the artist, who insists on the fact that the meeting already means the work itself. “We don’t need to be in Roraima or Paraná to learn about our history, we can be anywhere, and this process of returning to the Wapishana land is not an individual journey, it’s a relationship.”