The jaguar, also known as panther-jaguar, onça-pintada, jaguarapinima, jaguaretê or canguçu, is the largest feline in the Americas. Since it is at the top of the food chain and demands large preserved areas to survive, this animal has always been important in environmental conservation actions. For scientists, their presence indicated that a region preserved healthy biodiversity.

The narrator of Meu Tio o Iauaretê, by Guimarães Rosa, claiming to be related to a jaguar, says that it often changes its living area, “because the eating is not enough…”. When cattle raising, logging, monocultures, mining and illegal gold-digging arrive, jaguars are “moved far away.” The rule had always been: where there are jaguars, there is maintenance of flora, fauna, rivers and springs. No longer.

A study by the Federal University of Pará (UFPA)study published in January by researchers at the Federal University of Pará, which monitored felines in Paragominas, in northeastern Pará, points out that the species are adapting to environmental degradation in the Amazon. This feline, archetypal of power, which in the cosmogony of the Yawalapiti people, from the Upper Xingu, is the father of the twins Sun and Moon – who in turn are the parents of human beings – and is the only animal that has no fear or respect (kawíka) towards humans, is no longer a way to assess forests’ and biomes’ preservation level.

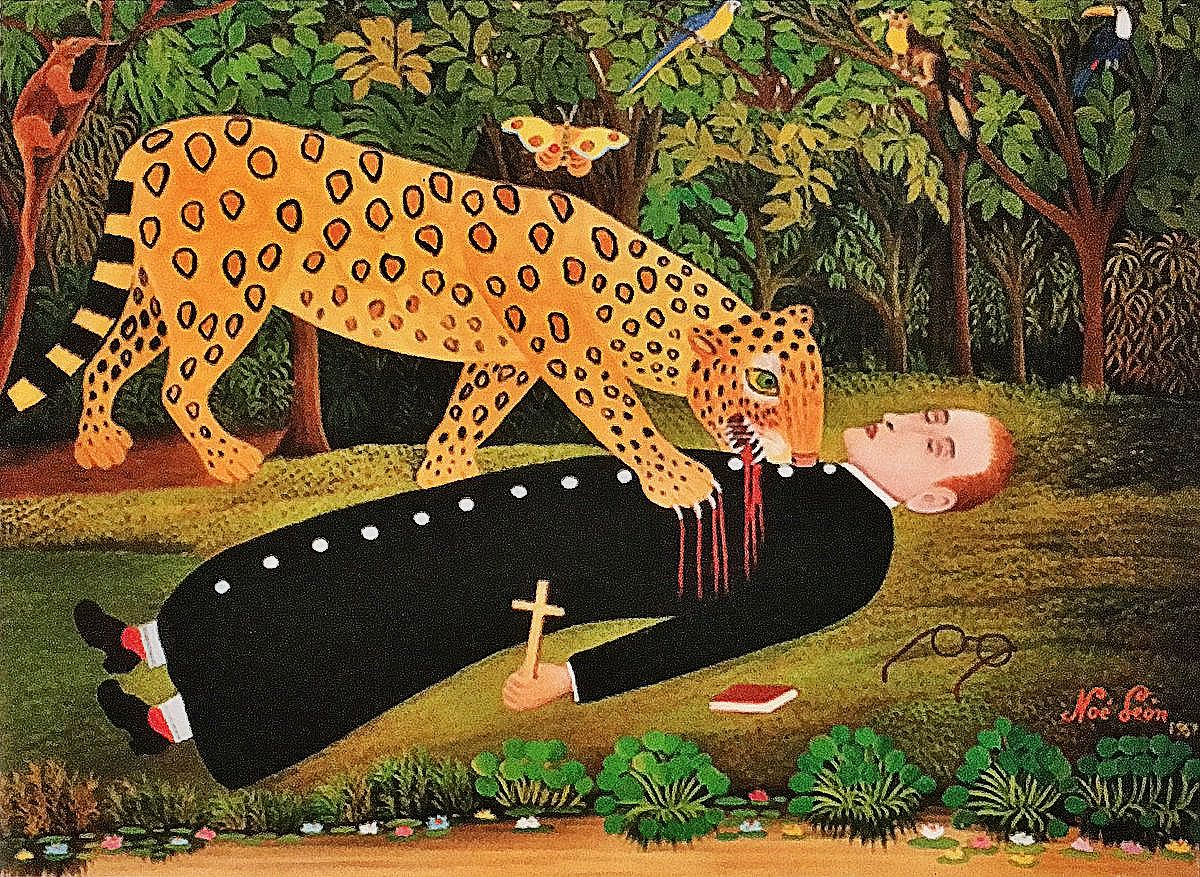

When an archetype of fearlessness has to submit to exploratory rules in order to not being extinct, changing its habits to adapt to human impact and survive in scorched land, it is worth remembering the cosmogonies which narrate the destruction of the original earth by cataclysms in the form of fires or floods. And to think about the transmutation ability attributed to this feline in the myths and how this transformation has been a key to indigenous resistance.

Mythologies about the jaguar find parallels with scientific thought. If the presence of large carnivores implies a rich and healthy ecosystem, for the indigenous people this animal represents an advanced state of understanding of time.

Unlike the big cats in other biomes, the jaguar can run, climb trees and swim with great skill, being able to capture prey in all of those spaces. This variety of resources, combined with its predominantly nocturnal habits, implies in strength, skill and a hunting strategy. This set of characteristics makes the jaguar a symbol of power and knowledge.

Resistance and destruction

Artist Yná Kabe Rodriguez Olfenza uses images of the jaguar in an analogy to transvestility: both are threatened, watched and experience transformation processes in their bodies. “We are felines too”, she tells seLecT. In her master’s thesis, “Táticas de Resistência: Relatórios da Sobrevivência da Onça”, (Resistance Tactics: Reports on the Jaguar Survival), Yná Kabe develops these parallels, commenting on the transvestites’ habit of wearing jaguar-print clothes. In the project “Secretaria para o Desenvolvimento da Primeira Escola de Indisciplina do Brasil” (Secretariat for the Development of the First School of Indiscipline in Brazil), the jaguar is a symbol of resistance in the most diverse causes, from deforestation to epistemological violence.

More than an animal, the jaguar is an entity that lends its destructive force to the world and to other beings. For good or for bad. For the Baniwa, the jaguars (Dzawi) saw the universe being born and have been here since the beginning. They saw the passage of time and understand it differently, have access to privileged information and are only preceded by the harpy eagle (Kamathawa), which flies over the world and informs Ñhapirikuli and Amaro, the couple that formed the world.

For the Kayapó people, in immemorial times, it was the owner of the bow, the arrow and the fire, until they were stolen by human beings. Deprived of weapons, it began to hunt with its teeth, and from the fire only a sparkle in its eyes was left. In the Tupinambá myth, restored by writer Alberto Mussa in Meu Destino É Ser Onça (My destiny is to be a jaguar), the apocalypse would happen when Sumé, an ancestral native, transformed into the great blue jaguara, the celestial jaguar, devoured the moon, extinguishing the night light, extinguishing humanity.

According to artist Jaider Esbell, for the Makuxi people the jaguar is an oppressive challenge and puts society on alert and vigilant. It is complementary to the tortoise: one is strength and aggressiveness, the other, parsimony and patience. And peoples try to balance themselves by leveling these two forces. “They work together for this greater reflection: the jaguar representing, for example, capitalism, globalization, colonization; and the tortoise bringing answers to what we can’t achieve through brute force,” says the artist. “This dichotomy represents how to deal with urges, anger, bitterness, how to use wisdom for our countercolonization work,” he summarizes.

Primordial and supernatural

Artist Sãnipã says that hãkytxy (jaguar) is a being that the Apurinã understand as a supernatural goddess. “She is a shaman, and when a mēēte Apurinã (shaman) receives the jaguar stone, he is prepared to take care of his people. If you need to go into the forest to get medicine, the jaguar will indicate where you’ll find it,” she says to seLecT. “The Apurinã shamans always talk to the jaguar, and when they die, they only die to our eyes. Spiritually, if he received the jaguar stone, then he will become a jaguar.”

For the Baniwa people, before human beings existed, the world was ruled by gigantic beings that, today, we understand as animals, but that were also people at the time. The jaguar is one of those beings who left this world for man to live here, but he can be accessed through the shamans, translators of these two universes. When the Baniwa shaman reaches the world of primordial jaguars, he is formed and receives the title of Pajé-Onça (Jaguar-Shaman), which is the highest possible training for human forms.

He then becomes more powerful, as he has gone through various trainings and experiences that no other human would endure. Seu Mandu (Manoel da Silva), the last jaguar-shaman Baniwa, passed away three years ago and helped build a shaman school, Malikai Dapana, on the banks of the Ayari River, in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Amazonas. In addition to preserving its knowledge and traditions, the school works to resist the violent arrival of Protestant churches in the region.

“I understand the role of an artist is of translating worlds, translating the Western to indigenous and translating Baniwa to you,” says Denilson Baniwa. “When I dress as a shaman, I’m doing these translations and putting myself at the disposal of this ancestral being to tell about the cycles of end of the world that already happened and that may come back if we’re not careful,” completes the artist, about the performance Pajé-Onça (2018), in which he walks around the city of São Paulo armed with a spear, rattle, jaguar head and cape.

Forest in the sky

The jaguar’s voracity is also in the celestial constellations, where this queen of the food chain is equally feared. A Tupi-Guarani people myth reports that the jaguar (xivi, in Guarani) always chases the Sun and Moon siblings. On the occasion of the solar or lunar eclipse, the indigenous people ritualize to scare the Celestial Jaguar, because the end of the world will come by when it devours the Moon, the Sun and other stars.

Also in the sky are the tapir, rhea, snake, deer, seriema, tortoise, armadillo, anteater and other animals. For the Ticuna people, the jaguar constellation is located near the Scorpio and the head of the anteater in the Southern Triangle. They claim that the fight between the jaguar and the anteater takes place during the dry season (from July to August, the ebb season), to avoid the eclipse of the Sun.

In early summer, the jaguar is on top of the anteater, and in the end the anteater appears victorious over it, before both animals leave the visible celestial sphere to give way to the ascent of the tortoise. In heaven, strength and prudence interact as if they were in the forest.